- Realism

- Detail

- Generality

- Match

- Precision: how quantitatively precise a model is in it's predictions

- Tractability: how analyzable or manipulable a model is

- Integration: Can it be used together with other models?

- Level: Cellular, population, strain...

- Medium

Tuesday, 26 January 2021

Behavioural modeling

Friday, 22 January 2021

Types of animal welfare studies

When talking about animal experiments, it's easy to start thinking along the lines of mice, needles and electric shocks. But there are naturally a lot of other kinds of experiments as well. Consider a simple case where an animal is offered two kinds of food to see which one they choose first. That is also research on animals!

The study of animal welfare is a very complex field. Just to start with: what IS welfare and how to measure it when the animal itself cannot talk or describe it's emotional states? Obviously a complicated set of research methodologies is needed to achieve robust results. The measurements taken to achieve the results can be roughly divided into two: physiological and behavioral.

| Physiological | Behavioral |

|---|---|

| Temperature Heart rate Blood glucose Fat percentage Weight Bacterial count | Time spent sleeping Frequency of a specific behavior Posture changes Social contacts Time taken to approach objects Distance traveled to forage |

As you can see, welfare can actually be quite specific!

Next, let's have a look at some types of studies which are conducted to find out more about animal welfare. All of the measurements listed above are just data, but it's of course important to know how to gather the data to make sure - you guessed it - that the data is correct. So what kind of experiments are used?

Preference studies

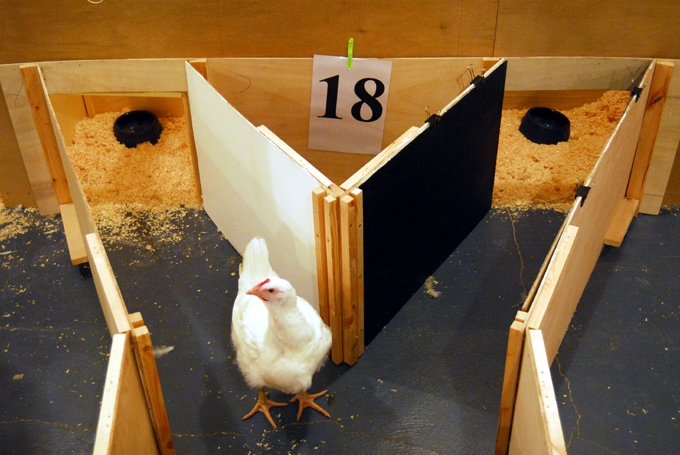

Preference and motivation studies are both examples of empirical study, where the researcher gathers data on the target of their study. In preference studies the animals choose what they prefer and what factors influence the preference.

An example of preference study is to offer chickens feed with and without NSAIDs (painkillers). Chickens with healthy feet eat more of the feed without medication, while chickens with leg sores and ulcerations prefer the feed with the medication (self-medication). Factors affecting the preferences can be available time, diet, health and pregnancy.

(c) Louse Buckley, UFAW

Motivation studies

Motivation study measures the motivation or willingness of an animal to reach a specific goal. The aim is to find out the value of things and what impacts the motivation. For example, an animal might be very motivated to get a treat when alone, but less motivated when they're in a group and know they might need to share their treat. Measurements can be speed and distance traveled to the goal, latency before the animal tries to reach the goal and energy spent to reach the goal.

In classic examples animal can be trained to press a lever to get a specific treat. Then the treat is disabled, and the amount of times the animal presses the lever trying to get the treat is the "price" they're willing to pay for it. Things like temperature, eating, health and group size can all affect the value of the reward.

Metastudy

Metastudy is different from the other types, because this is the study of studies. In metastudies the researchers gather a vast amount of previous researches, carefully select the most relevant ones and summarize their findings. The process of selection and omission must naturally be well documented and argumented. The aim is to see wider trends and generalizations. Commonly seen phrases like "many studies prove" or "there is little scientific base on the claim that" arise from metastudies. Metastudy goes further than just being a literature review. It uses for example statistical methods to compare the results of the studies once comparativeness is established.

More information:

Animal welfare science - Wikipedia

Consumer demand tests (animals) - Wikipedia